Manual Therapy Online - Articles

Script Focused Deduction: Mimicking the Expert

For the most part teachers of manual therapy, and I include myself here, tell the student to gather as much information as possible before coming to a solution or a decision. On the face of it this seems sensible but when we say this we completely ignore the fact that this is the exact opposite of what we do in the clinic. When faced with a clinical problem the expert, and it seems only reasonable to assume that all teachers are experts to some extent, will gather only the information needed to solve the problem. Minimal information is the name of the game and for the most part it works extremely well providing the expert is truly knowledgeable and experienced in the area that encompasses the problem. But rather than teaching the student how to do this we teach them to do the exact opposite. Again on the face of it this seems the only thing to do, you cannot infuse novices with the knowledge of experts and experience, by definition must come with time and exposure to the problem, having success with it and most importantly failing and learning from those failures. But it must be possible to teach the novice how to mimic the expert by using minimal information that is both extremely sensitive and specific to the patient’s problem. I think this is true and I also think it is not necessary to invent a whole new process but to modify and fuse existing processes. These procedures are:

- Thin slicing

- Illness scripts

- Hypothetic-deduction

- Bias/error correction

Using the principles of thin slicing we are going to use the least amount of information that will yield the diagnosis. This means that the pertinent part of the patient profile (age and gender) and the presenting complaint of the patient is the basis for everything following. We can admit to needing more information before making a decision but not to making a testable hypothesis (sorry for the redundancy). The hypothesis can be turn out to be completely wrong and it doesn’t matter but for efficiency’s sake the hypothesis should be based on where the pain is experienced and on prevalence, that is what is the eventual diagnosis is most likely to be. The first test of the hypothesis will be the patient’s profile, “can the condition that is being hypothesized occur in the patient’s gender group” and “ is the age a barrier to proving the hypothesis?” questions that should be asked. If the barrier presented by the profile provides a better fit for the patient’s complaints then this should replace the initial hypothesis.

Let’s take a very simple example: a 48 year old man complains of right lateral elbow pain. The considerations are; which structures lay under the pain area and is it possible that this pain is referred from the neck or the shoulder? Underlying the pain is the common extensor tendon, the humeral epicondyle and the lateral compartment of the elbow joint complex (the most likely of these structures to be the pain generator based on prevalence is the common extensor tendon. How likely is it that the pain is referred from the neck or shoulder? To determine the probability of this we need to consider if the pain at the lateral elbow is contiguous with pain from either of these two regions. If not then referred pain is much less likely than local pain but even if we are wrong in this conclusion we will discover that as we proceed with the hypothetic-deductive phase of the process. In this example there is only lateral elbow pain so a local hypothesis is the most likely and based on prevalence H1 equals common extensor tendonopathy.

If thin slicing is not possible, that is the clinician has never before come across a similar symptom or patient profile previously (hardly likely in this case) then traditionally a full and exhaustive objective and subjective examination is carried out in the hopes that something enlightens the therapist (more likely is that bias will assert itself and an incorrect diagnosis is made) or more effectively and efficiently a second opinion is sought.

Using SFD once the first hypothesis (H1) is made it can be tested with a modification of the illness script to see if it can be converted to a diagnosis or if a better fit (H2) needs to be generated and tested.

As we saw earlier the illness script is not so much a method or tool of clinical reasoning but a description of a process occurring during clinical reasoning. The clinician holds a picture of the presentation of a particular condition in her/his head that is richer or poorer depending on the clinician’s experience and studiousness that is compared to what the patient is relating and demonstrating. If they fit the diagnosis is made if not then befuddlement ensues. Not practically very useful but if the illness script of the common presentation of the condition is boiled down to the minimum necessary to accurately describe that variation then this essential illness script (EIS) can be used to test the hypothesis. In effect the patient’s initial complaint is the sensitivity component of what will become a cluster of tests (subject and objective), being 100% sensitive to the patient’s condition. The rest of the history can now concentrate on specificity while the objective tests should be sensitive and specific. As a general rule of thumb 4 questions and 2 tests would provide the sensitivity and specificity needed to diagnosis the common presentation of the condition; anymore than the minimum and specificity suffers.

In this example H1 is tennis elbow so we need a few questions that would strengthen the hypothesis. The complaint, lateral elbow pain, defines the question, where is the pain and is 100% sensitive for this patient’s condition, it must be. So we attack H1 with the EIS of tennis elbow;

- Lateral elbow pain

- Hand function (gripping) is significantly worse than elbow movements

- Tenderness of the common extensor tendon

- Isometric wrist extension painful

In this case we only need two questions and two tests to confirm or refute H1 as there really isn’t anything that is a better fit (whether this is a tendonosis or tendinitis will have to be determined after tendonopathy is established as the diagnosis).

Let’s assume that of the four features one was not present, how badly does this weaken H1? If a better fit is available based on the incoming information then H1 needs to be scrapped and replaced by H2. If, on the other hand H1 is weakened but not disproved and is still the most viable hypothesis then H1 needs to be modified to describe a less common variant of the condition. In this example a deviation from almost any of the above four features would require H2 if one can be found. For me it would likely be a radiohumeral joint dysfunction and/or arthritis, in which case H2 needs to be tested by the EIS of radiohumeral joint dysfunction. But we are doing well and all four features of the EIS of tennis elbow are present and we promote H1 to a diagnosis (Dx).

This process has involved knowledge of anatomy, pathology and prevalence to provide H1, and hypothetic-deduction as we attacked the hypothesis with the EIS. But finally before we enshrine the Dx in a treatment we should test for bias and error.

The main bias’ we have to be concerned about are (we will cover this more completely in the next essay):

Premature satisfaction (premature closure or search satisfaction), anchoring, framing and regression to the familiar. How to counter these biases have already been described in general terms but let’s work them through the example of tennis elbow.

Premature satisfaction is countered by a full examination of the elbow. All ranges of motion, isometric tests, ligament stress tests and neurological function tests. In addition a biomechanical examination may be undertaken, passive physiological and passive arthrokinematic (accessory) movement tests or at least a sensitive screening test such as quadrant scouring. But these must not be done to make the diagnosis just to check that your biases haven’t imposed themselves and made you misdiagnose the problem.

Framing is avoided by not asking the patient about his/her work, previous history, physician’s diagnosis, previous treatments, method of onset or about other non-contiguous pains. Only consider the patient’s age and gender and the initial complaint, you will not miss anything as the hypothesis testing stage will reveal what needs to be revealed and if this doesn’t then the full examination to eliminate premature satisfaction will do so.

Availability and anchoring bias can be reduced and even eliminated by generating a list of differential diagnosis (DDx) and giving them due consideration in the light of what information has come in as you test H1 or subsequent hypotheses. In this case the table below will demonstrate the process.

| DDx | Cons based on DDx EIS | Viable |

|---|---|---|

| Articular dysfunction | Pain on elbow rather than hand function Joint not tendon tender |

No |

| Lateral ligament tear | Pain on elbow rather than hand function Ligament not tendon tender Isometric wrist extension not painful |

No |

| Referred | Contiguous pain absent Local tests positive |

No |

| Fracture | Elbow movements provoke severe symptom | No |

| Arthritis | Elbow movements provoke severe symptom | No |

I have only listed the cons, as the pro is always the same; the pain is lateral elbow pain. The simple act of considering these other possibilities reduces bias.

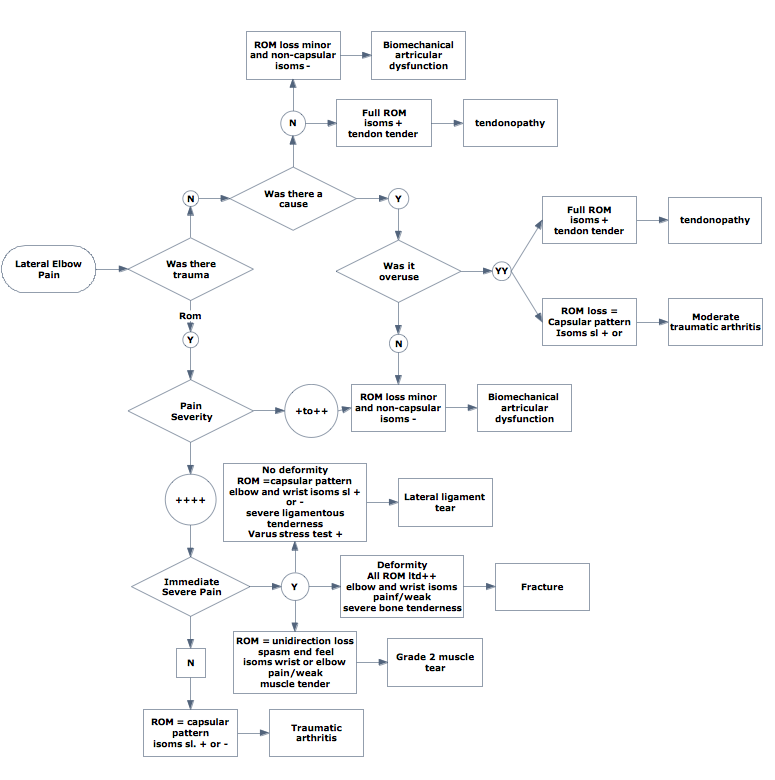

We can compare the two methods in diagrammatic form using flow charts. First the traditional method using hypothetic deduction. Obviously not all possible results of all tests have been included but even this very cut-down diagram is sufficient to demonstrate how complex this method can be.

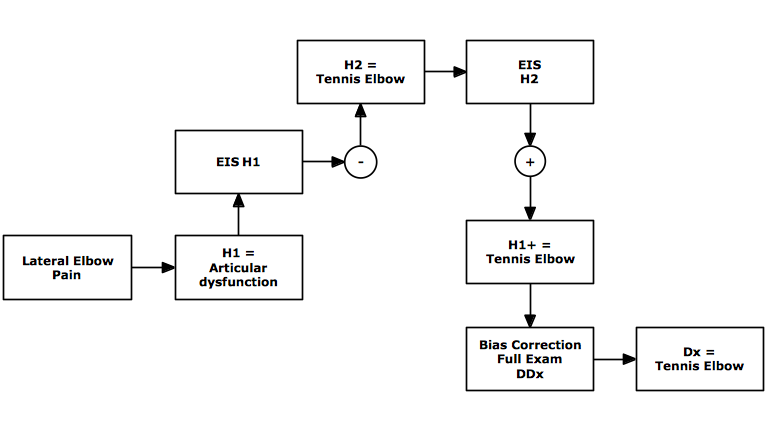

Script focused deduction with a disproved first hypothesis would look something like this.

As can be seen even when an incorrect hypothesis is tested first this process is much less complicated and more importantly less confusing. This is because the process is focused on the currently held hypothesis and does not require information that will not directly illuminate it. If this information is needed it will be because the hypothesis has been changed to one that has that information in its EIS.

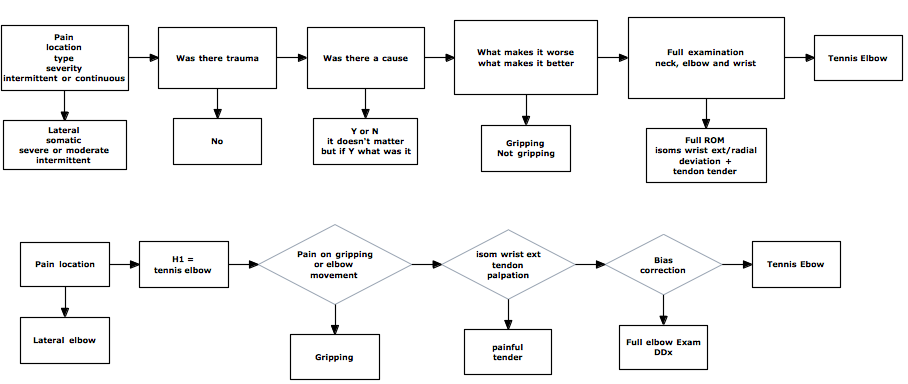

A very condensed comparison would look like below.

Left out of the traditional exam’s flow chart are questions about past history, medications, family history, occupation, liesure activities etc., which would increased the number of questions asked over the ten or so listed about to probably 20-25 depending on the answers. For example tell me about your family history must lead to numerous questions about each condition and each family member related by the patient. SFD initially on requires answers to that of the EIS at most 4 and in this case 2. While the others questions may be important from the perspective of etiology and treatment contraindications they are unecessary to make the diagnosis of tennis elbow.

It is apparent that there are four elements critical to script focused deduction:

- Accurate essential illness scripts

- Confidence to make the first hypothesis on very limited information

- Willingness to discard non-viable hypotheses for one with a better-fit to current information

- Willingness to admit that you might be wrong and investigate that possibility

- Essential illness scripts need to be drawn from the appropriate literature, experience, yours and other’s. If it is a medical condition use medical rather than physical therapy texts unless the latter is taking the information from the medical literature. The scripts need to be short so as to be specific but there must be at least one sensitive question and test .

- The confidence to make a hypothesis from minimal information is essential and this is were breaking conditioning really comes in to play. We practice most comfortably that which learn first and we are taught to gather all information before making a decision and to a point that is correct but insert one more word in that teaching, “relevant”. You should only gather the information you need to complete a given task not that which is necessary to a different task. Here you should be focusing on making a diagnosis, not finding an etiology or worrying about their societal support system or even contraindications to treatment.

- The willingness to change hypotheses when it has been disproved is another area where bias can dominate if allowed. Changing hypothesis is seen by many as a failure but of course it is not. The failure is to give inappropriate treatment because of a misdiagnosis. Actually the more often you change the hypothesis the more focused information you gather and so the likelihood of success improves. Clinging to a failed hypothesis is a form of anchoring and will lead to mistreatment.

- Willingness to admit that you might be wrong and investigate that possibility is vital in all forms of problem solving but especially in diagnosis. Wrong diagnosis is most likely to be caused by bias; not gathering all pertinent information (premature satisfaction), clinging to a failed hypothesis (anchoring), making everything that you don’t understand fit your favorite diagnosis (regression to the familiar) and information gaps or or misinformation.

Featured Course

FREE COURSE

Foundations of Expertise

Date:

Starting March 24, 2024

Location: Online

LEARN MORE